“Non-Plus Ultra”, ‘Cebelitarık Boğazı ’nı bilinen dünyanın sınırıyla ilişkilendiren, tarihte dikkate değer bir noktaya işaret eden kelimelerdir. Bu eski metafor, V. Charles tarafından ‘Plus Ultra’ olarak yeniden yorumlanmış ve uzun süredir devam eden tabuyu, Atlantik’in diğer yakasının İspanya’nın egemenliği altında olduğunu ifade eden güçlendirici bir bildiriye dönüştürmüştür [1].

Endülüs, Vikingler, Fenikeliler, Romalılar ve Müslümanlar da dahil olmak üzere çeşitli uluslar ve etnik gruplar tarafından yönetilmiş olan çok kültürlü bir bölgedir. Benzersiz jeopolitik koşulları nedeniyle bölge, farklı kültürlerin zengin bir etkileşimine tanıklık etmiştir. Ancak en önemli kültürel alışveriş Müslüman otoritelerin yönetimde olduğu 8. ve 15. yüzyıllar arasında gerçekleşmiştir. Bu yazı, “iç içe geçme teorisi” kavramını yalnızca kültürler arasındaki sosyal bir değişim olarak değil, aynı zamanda farklı ölçekler ve dönemler boyunca mimarinin fiziksel bir tezahürü olarak da incelemektedir. Yazı üç bölüme ayrılmış ve her bölümde sırasıyla Sevilla, Cordoba ve Granada şehirlerinin mimari varlığı ele alınmıştır. Bu şehirlerin tarihi ve çağdaş mimari zenginlikleri bir mimarın bakış açısından incelenmiştir.

Bölüm 1: Başkent

Mudejar tarzı süslemelerle bezenmiş zarif sarı Rönesans cephelerinin sıralandığı dar şehir koridorlarında ilerledikten sonra ziyaretçileri geniş bir meydanda yer alan Gotik tarzdaki muhteşem bir kilise karşılamaktadır. Orijinalinde camii olarak inşaa edilen La Catedral de Sevilla, Endülüs’teki iki farklı dini mimari tarzın karışımını sergileyen ikonik yapılardan biridir. Orijinal caminin büyük bir kısmı kilisenin inşası için yıkılmış olsa da, ikonik minare ve portakal ağaçlarıyla dolu avlu İslam mimarisinin etkisinin kalıntıları olarak durmaktadır [2]. Katedral, 15. yüzyıldan başlayarak çeşitli inşaat aşamalarından geçmiş ve 17. yüzyılda tamamlanmıştır. Bu durum, Barok, Rönesans, Gotik ve İslami özellikler dâhil olmak üzere tek bir yapı içinde farklı mimari tarzların karışımını beraberinde getirmektedir.

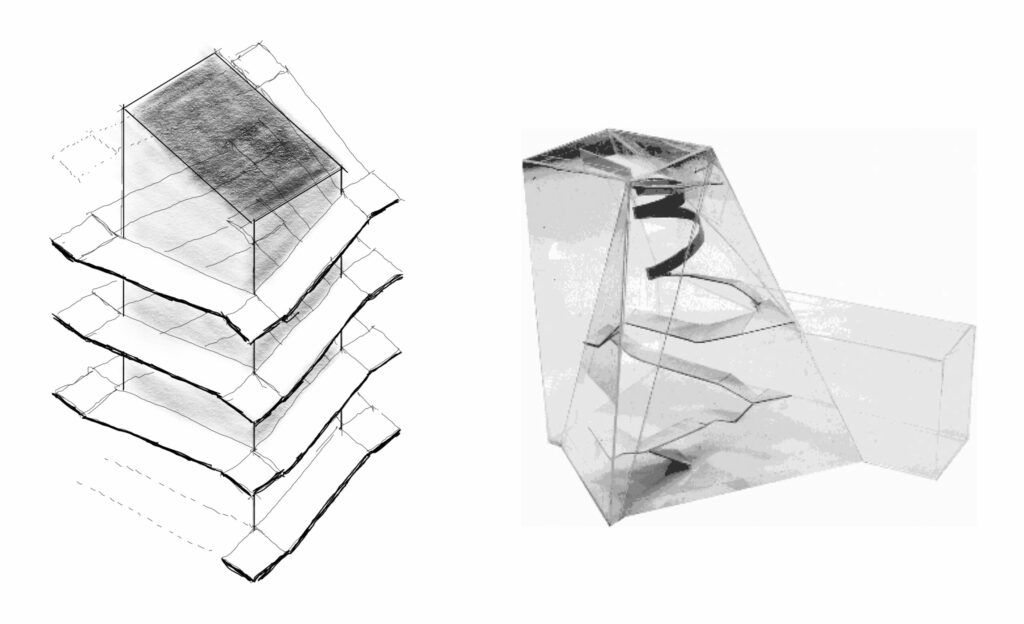

Kulenin tepesine çıkmak için dar ve eğimli koridorlardan yukarı doğru hareket ederken, Sevilla’nın çarpıcı perspektifleri dar pencereler araclığıyla sunulmaktadır. Eğimli koridorlar boyunca uzanan açıklıklar ve nişler, şehrin eşsiz perspektiflerini sunmakta ve zirvede muhteşem bir panoramik manzarayla sonlanmaktadır. Benzer bir deneyim Tate Modern’in merdivenlerini tırmanırken de yaşanmaktadır. Bodrum katından başlayarak kesintisiz devam eden sirkülasyon merkezi, ziyaretçilerin şehri çeşitli bakış açılarından deneyimlemelerine olanak tanımaktadır.

Flamenko melodilerinin at arabalarının ritmik vuruşlarını takip ettiği, insan sohbetlerinin havada dans ettiği ve su seslerinin insan ruhunu beslediği Plaza del Triunfo’dan,” Aslanlı Kapı”, 11. yüzyıldan kalma kırmızımsı duvarlarıyla göz kamaştırmaktadır. Kapıya yaklaşırken, iki gözlem kulesi, yapının ağırlığını azaltmak ve yapısal hareketleri absorbe etmek için küçük taşların üstün tuğla işçiliğiyle dikkatlice birleştirildiğini göstermektedir [3].

“Av Avlusu”na ulaşmadan önce ziyaretçiler “Aslanlı Avlu”dan geçen merkezi bir eksen boyunca yönlendirilmektedir. Bir yangında yok olana kadar, “Corral de Comedias de la Montería” olarak bilinen tiyatro, eliptik zemin kat planıyla tüm avluyu kaplamaktaydı [3]. Mevcut merkezi eksen I. Pedro tarafından oluşturulmuş ve ziyaretçilerin üç farklı dönem, üç mimari tarz ve üç cepheyle çevrili ana avlu ile doğrudan etkileşim kurmalarını sağlamıştır. Kompleksin tamamı Mağribi ve Gotik mimari unsurların karışımıdır ve çok kültürlü bir yapı içinde kültürlerin ve insanlığın iç içe geçtiği bir nokta olarak hizmet vermektedir.

Bu deneyim boyunca ziyaretçiler egzotik ağaçların kokusunu alabilir, suyun yumuşak hareketlerinin sesini duyabilir, doğanın huzurunu hissedebilir ve muhteşem yapılara hayran kalabilirler. Real Alcázar yapay bir cennet, şehrin ortasında bir vaha olarak tanımlanabilir. Bir zamanlar tek bir aileye ya da bireye ait izole bir saray ve kaleyken, şimdi nefes almak, öğrenmek ve iyi hissetmek için bir eşsiz bir atmosfer sunmaktadır. İnce işçilikli mimari özelliklere sahip cephelerle çevrili avlulara ek olarak, geniş bir park ve kompleksin bitişiğindeki bir dizi bahçe, şehrin ortasında ruhu canlandıran bir kaçış mekanı sağlamaktadır.

Rotayı Eski Kent’ten Guadalquivir Nehri’nin karşı tarafına çevirirken hedef Torre del Oro’ya ulaşmaktı. Yaldızlı yazılarla süslü taş kaplı cephesi daha kuleye varmadan dikkatleri üzerine çekmektedir. Rafael Moneo tarafından tasarlanan Previsión Española binası, Sevilla’daki çağdaş mimarinin bir sembolüdür. Şu anda Helvetia Seguros tarafından kullanılan bu ofis binası şehrin nehir sınırında yer almaktadır.

Previsión Española, Almohad döneminden kalma tarihi surlara saygı gösteren bir tasarıma sahiptir [4]. Duvarı andıran rijit yapısı ve ince tasarım öğeleri, Almohad mimarisine atıfta bulunmaktadır. Kompleksin tamamı Torre del Oro’ya bir arka fon oluşturmaktadır. Sürekli bir pencere bandı, yatay taş şeritler ve betondan yapılmış beyaz korniş yatay tasarımı vurgulamaktadır. Narin dairesel mermer sütunlar ve kavisli tuğla duvarlarla desteklenen revaklı galeri, Real Alcázar’da bulunan Almohad mimarisini çağrıştırmaktadır.

Yatay mermer bant, cepheyi üst ve alt bölümlere ayırmaktadır. Müstahkem bir kaleyi andıran giriş, gözlem kulelerine benzer şekilde akılda kalıcı ve figüratif bir izlenim yaratmaktadır. Cephenin Almohad mimarisine yaptığı göndermeler ve tasarım özellikleri geçmişle güçlü bir bağlantı yaratmaktadır. Yapı, malzeme ve biçim açısından, yerleşik mimari ilkelerine bağlı kalarak kentsel dokuya sorunsuz bir şekilde entegre olmuştur.

Previsión Española, Torre del Oro’ya tamamlayıcı bir yapı olarak hizmet ederek kulenin varlığını vurgulamaktadır. Binanın mütevazı arka avlusu şu anda işlevsel olmayan bir otopark alanı gibi görünse de tıpkı Real Alcázar gibi farklı tarihi dönemleri birbirine bağlayan ilgi çekici bir kamusal alan olma potansiyeline sahiptir.

Bölüm 2: Süreklilik

Yolculuk, mimari üzerindeki İslami etkinin belirgin bir şekilde görünür ve hissedilir olduğu bir bölgeye doğru devam etmektedir: Cordoba. Bu şehir tarihi Müslüman hamamlarına, ünlü Mezquita de Córdoba’ya ve egzotik ağaç ve çiçeklerle süslenmiş büyüleyici yeşil avlulara ev sahipliği yapmaktadır. Cordoba’nın antik karakteri korunmuş olup, şehirdeki konutlar tipik olarak 2 ila 3 kat yüksekliğindedir. Organik kent dokusu, arnavut kaldırımı döşeli sokakları boyunca bulunan eşsiz güzelliği keşfetmeye davet etmektedir. Bu sokaklar ya sıvalı beyaz duvarlarla ya da çarpıcı Endülüs tarzı taş cephelerle sınırlandırılmıştır. Ziyaretçiler, Puente Romano olarak bilinen antik Roma köprüsünden geçtikten sonra Puerta del Puente yapısı tarafından selamlanmaktadır.

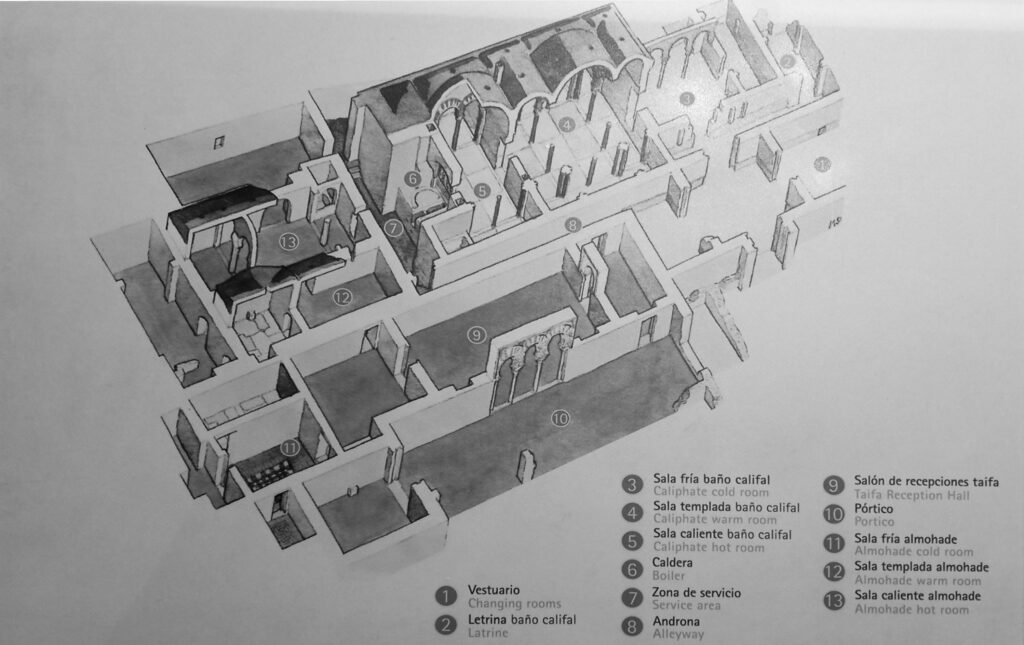

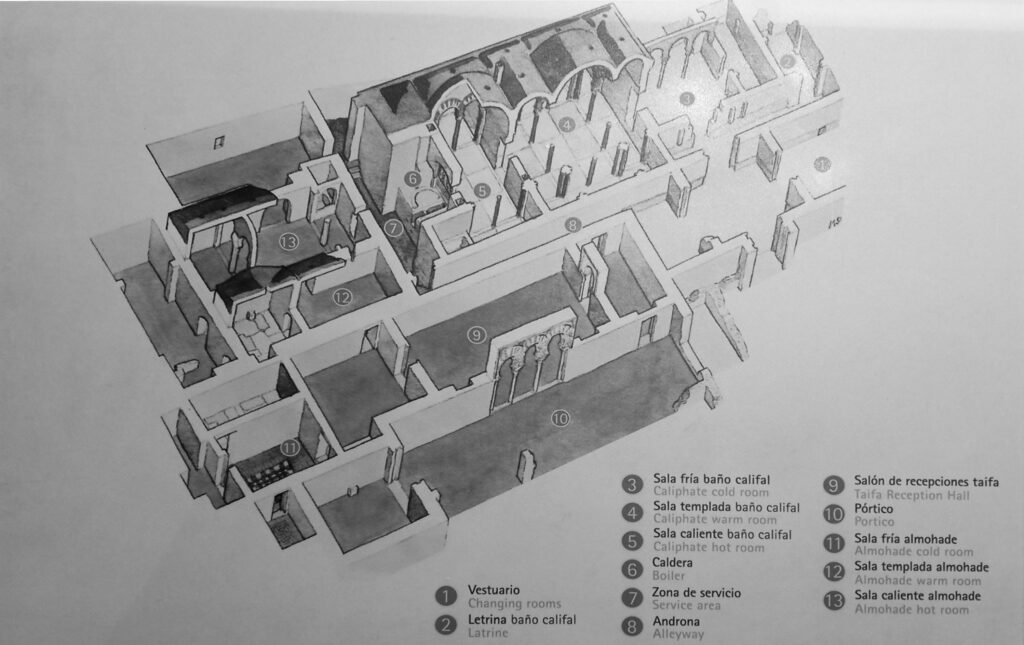

Dünyaca ünlü simgesel yapıya ulaşmadan önce ziyaretçiler, saray mimarisine örnek teşkil eden bir hamam yapısı olan tarihi “Baños del Alcázar Califal” kalıntılarının büyüsüne kapılmaktadırlar. Halife Sarayı’nın bir parçası olarak 10. yüzyılda inşa edilen bu banyolar emirlere ve halifeliğe hizmet etmiştir [5]. “Baños “un plan tipolojisi hem doğrusal hem de dolaşımsal bir yapıya sahiptir. Fiziksel arınmanın ötesinde, bu ritüel aynı zamanda ruhsal rahatlama sağlamakta ve zihinsel sağlığı geliştirmektedir.

Ritüel “Frigidarium” olarak bilinen dikdörtgen alanda başlar ve burada beden arınma sürecine hazırlanır. Daha sonra, “Caldarium”a girmeden önce, bireyler ilk olarak “Tepidarium”da zaman geçirirler. Bu oda dikkat çekici mimari detaylara sahiptir. En göze çarpan özellik, zarif kahverengi ve siyah mermer sütunlarla desteklenen at nalı kemerleridir. Bu sütunların dizilişi, merkezi mermer zeminin çevresinde küçük bir arkad oluşturmaktadır. Doğal güneş ışığı, tavandaki yıldız şeklindeki küçük bir tavan penceresinden odaya dolmaktadır. Ruhu besleyen yolculuk Sıcak Oda’da doruğa ulaşmaktadır. Tepidarium’a benzer şekilde, revaklı galeriler bu merkezi alanı benzersiz bir şekilde tanımlayarak kendine özgü karakterine katkıda bulunmaktadır.

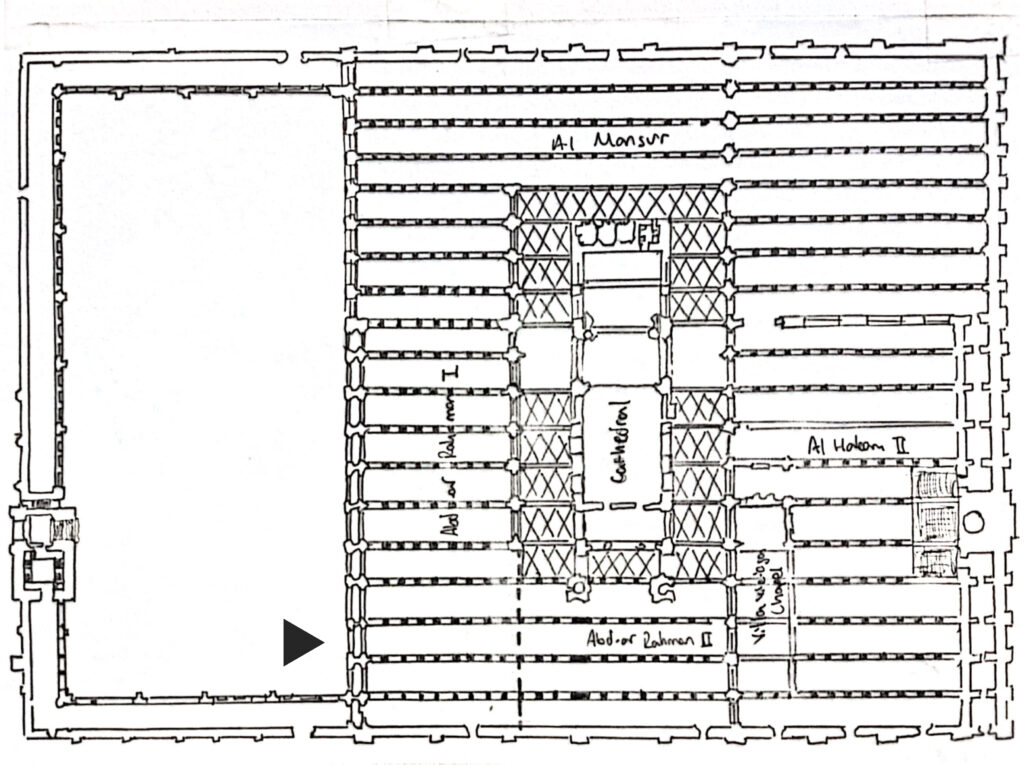

Doğrusal kanallarla birbirine bağlanan gömülü dairesel topraktan yükselen portakal ağaçları bir şemsiye gibi insanları güneşten korurken, insan sesleri ve kuş cıvıltıları 12. yüzyıldan kalma bir yapıyla sarılmış devasa bir avlunun içinde birbirine karışmaktadır. Burası, çeşitli halifeliklere, dinlere ve mimari tarzlara tanıklık etmiş olan Mezquita de Córdoba’dır. Şam Camii, insan ve Tanrı arasındaki ilişkiye dair yeni bir anlayışı yansıtan İslami “dini mekân” kavramını yaratarak daha sonraki birçok caminin topolojik modelini oluşturmuştur [6]. Buna karşılık Córdoba Camii, tüm etnik kökenlerden ve milletlerden insanları kucaklayarak İslam mimarisine yeni bir yön kazandırmıştır. Bir birlik tapınağı olarak hizmet vermektedir.

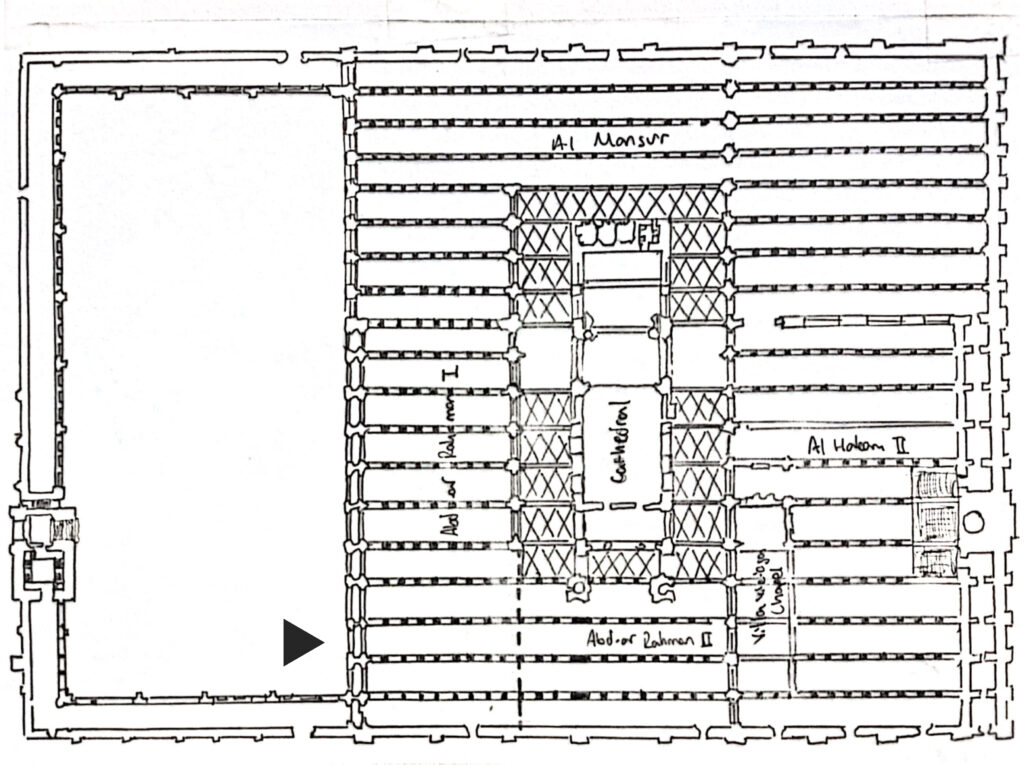

Córdoba Camii, 8. yüzyılda I. Abd Al-Rahman döneminde Şam’daki camilerden ilham alınarak inşa edilmiştir. Bazilika plan tipolojisini benimseyen orijinal mimari yaklaşımın sürekliliği on yüzyıl kadar korunmuştur. Abd Al-Rahman II döneminde ise camii yapısının korunması ve sütun kaidelerinin kaldırılması gibi gözle görülür müdahaleler yapılmıştır. Bugünkü mimarisinde ise caminin sonsuz yapay mekânları Tanrı’nın varlığını somutlaştırmaktadır. Hristiyan kiliselerinde bulunan (merkeziyetçiliği vurgulayan) “eksenellik” ve “sıralılık”, bu camide yerini nötr ve karakterize edilmemiş mekânlara bırakmaktadır [6]. Simetri ihtiyacı, soyutlama ve farklılaşmanın ortasında bile belli bir düzeni dayatmaktadır.

Abd Al-Rahman III döneminde minarenin inşasından sonra, en dikkat çekici genişletme planı Halife Al-Hakam II döneminde gerçekleştirilmiştir. Yapı, mihrap ve maksureyi özel ilgi odağı haline getiren yeni on iki bölümle güneye doğru genişletilmiştir. En yenilikçi eylem, dört tepe penceresinin inşa edilmesiydi. Caminin genel görünümü, süsleme olarak detaylı bitki motifleri, gösterişli mermer ve mozaik malzemeler kullanılarak zenginleştirilmiştir.

Almanzor son genişletme projesini gerçekleştirmiş ve yapı batıya doğru genişletilmiştir. Mimari değer açısından son proje camiiye çok büyük bir katkı sağlamamıştır. Kemerlerin aynı taş malzemeye sahip olduğu ve orijinal kemerlerdeki tuğla malzemenin kırmızı boya ile taklit edildiği fark edilebilmektedir. Sütun dizileri arasında Almanzor tarafından inşa edilen iki kalın dik duvar, camiye yeni bir okuma getirmiştir. Al-Hakam II’nin farklılaşmamış mekânı ve yönlülüğü seyreltilmiştir.

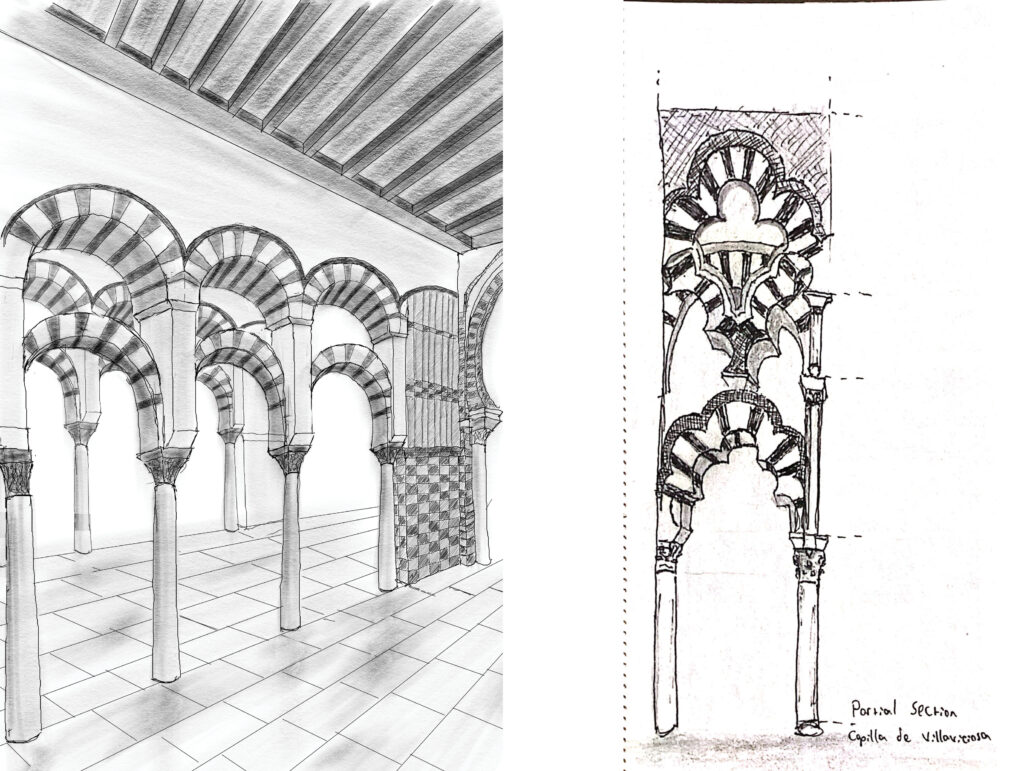

Capilla De Villaviciosa, Cordoba Camii’nin eski ve yeni parçaları arasında sanal bir kapı olarak hizmet etmekte, otantik bir eşik görevi görmektedir. Eksenel nefin üç bölümü, merkezi açıklıktaki bir çift sütunla tanımlanmıştır. Üç boyutlu elemanlara dönüşen ve üst üste binme mekanizmasına sahip delikli duvarları yapının statiği için büyük önem taşımaktadır. Mimari yapı burada karmaşıklığın ve güzelliğin doruğuna ulaşmıştır.

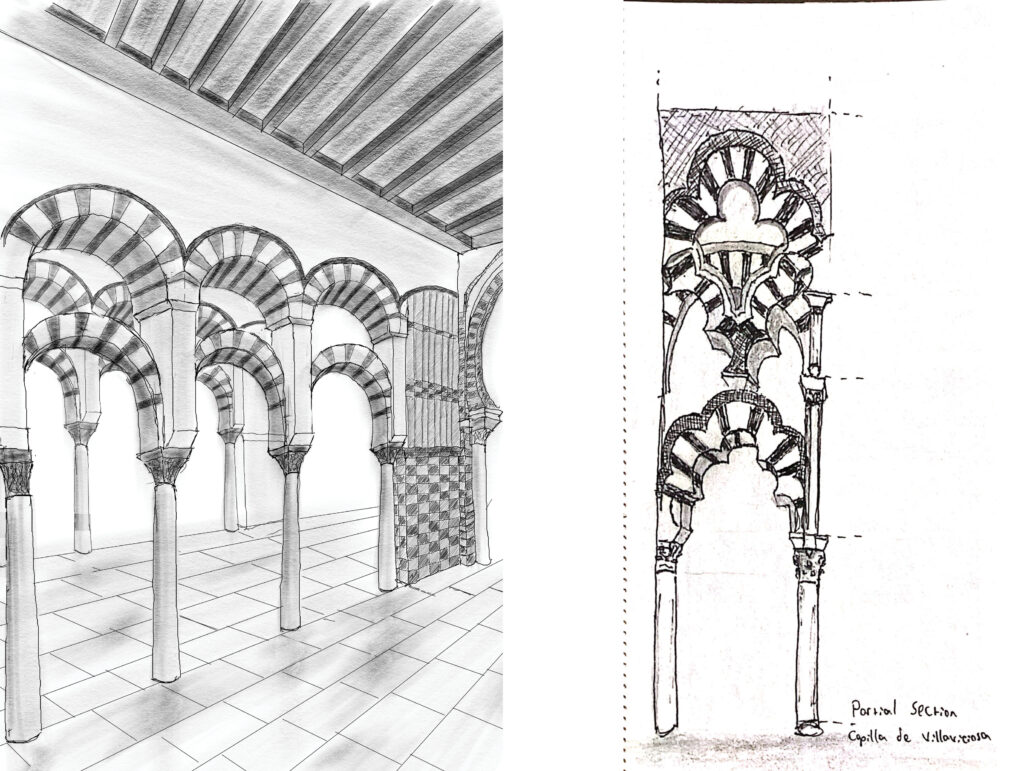

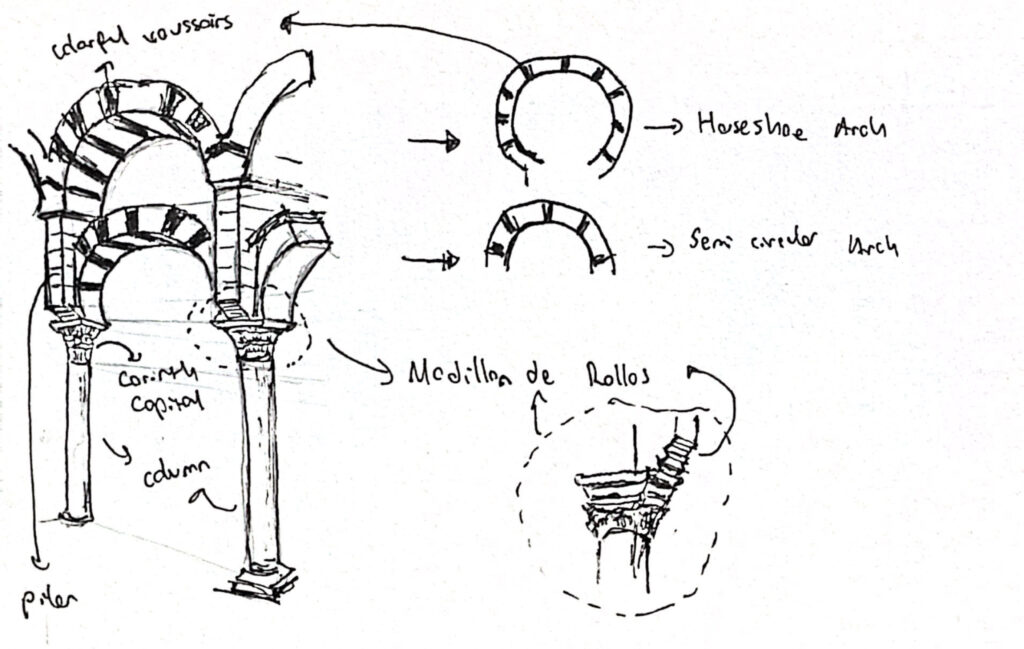

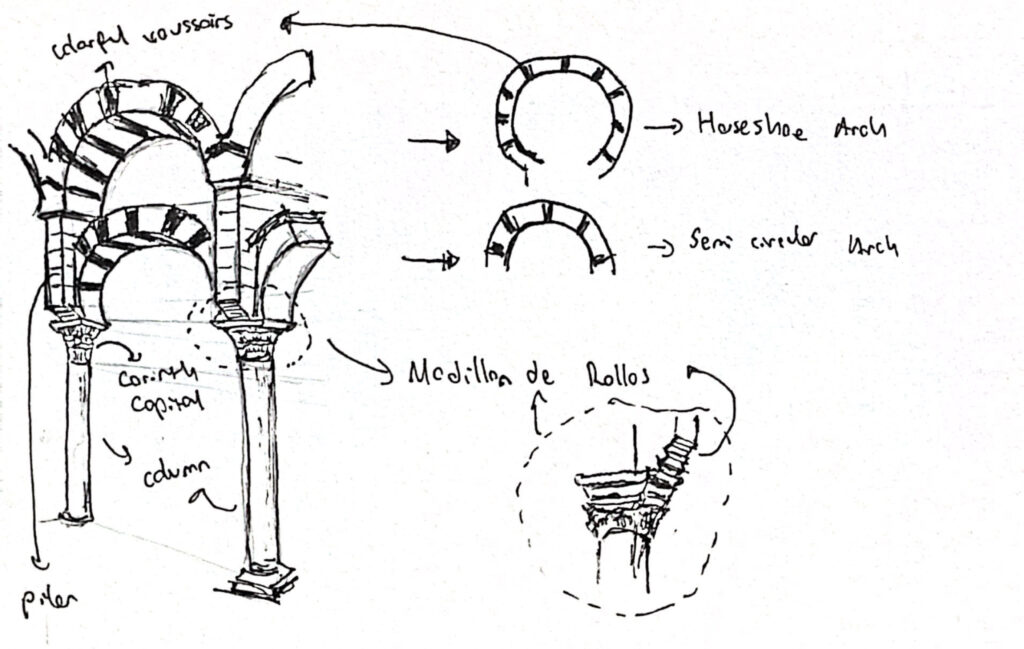

Cordoba Camii, kıbleye dik olarak uzanan ve nihayetinde mekânsal deneyimi şekillendiren bir dizi su kemeri duvarına sahiptir. At nalı kemerler yarım daire biçimli kemerlerle desteklenerek daha yüksek bir çatıya ve daha aydınlık alanlara olanak sağlamaktadır. Biçimsel yapı bu iki sistemin kesişimine dayanmaktadır. Mekanın sütunlar aracılığıyla tanımlanması yeni, nötr ve farklılaşmamış dini mekana özgün bir ifade şekli kazandırmıştır. Bunlara ek olarak, üst üste binen mimari formlar bu camiide uyumlu bir bütün halinde birleşmektedir. Örneğin Modillon de Rollos olarak bilinen unsur; sütun, sütun başlığı ve at nalı kemerin birleşim noktasını çözerek kare bir tabandan dikdörtgen bir tabana geçişi sağlamaktadır [7].

Bölüm 3: Sarayın Şehri

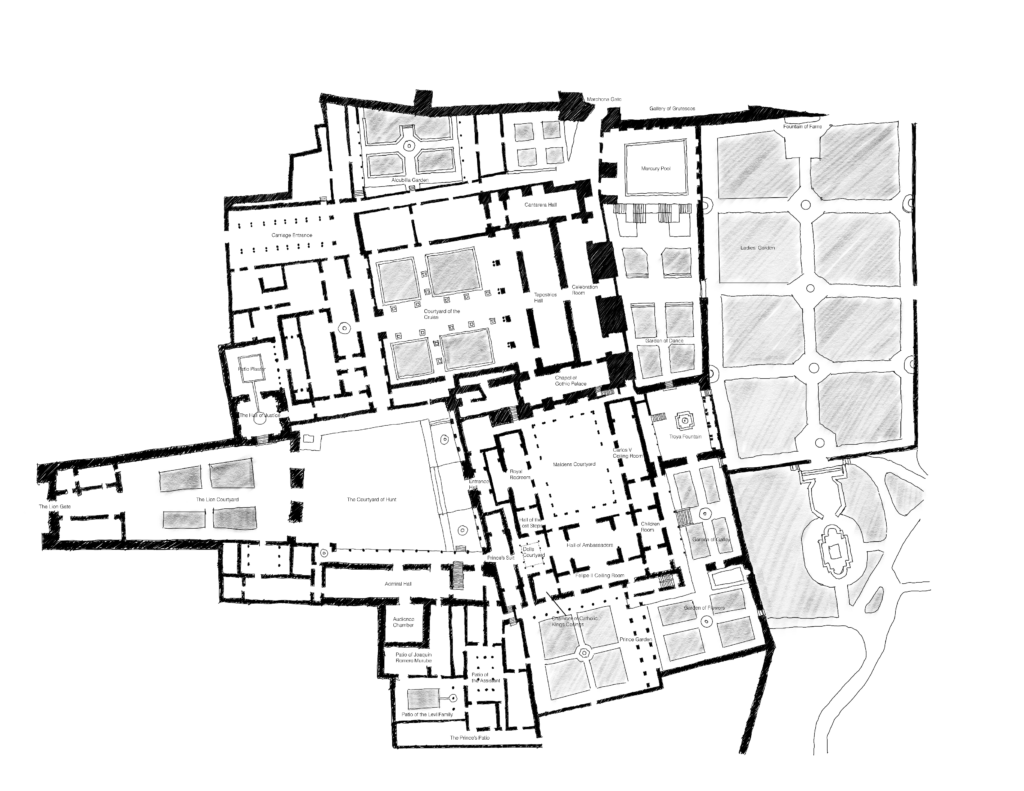

Yolculuğun son durağı, tarihi ve çağdaş mimari hazinelere ev sahipliği yapan Granada’dır. Granada’nın en önemli mimari unsurlarından biri “Kırmızı kale” anlamına gelen Elhamradır. Genel kanının aksine saray olarak bilinmesine rağmen Elhamra bir tekil bir yapı değil, komplekstir. Bu kompleks, Nasrid hanedanının kurucusu Muhammed I ibn Nasr’ın ikametgâhı olarak hizmet vermiştir [8].

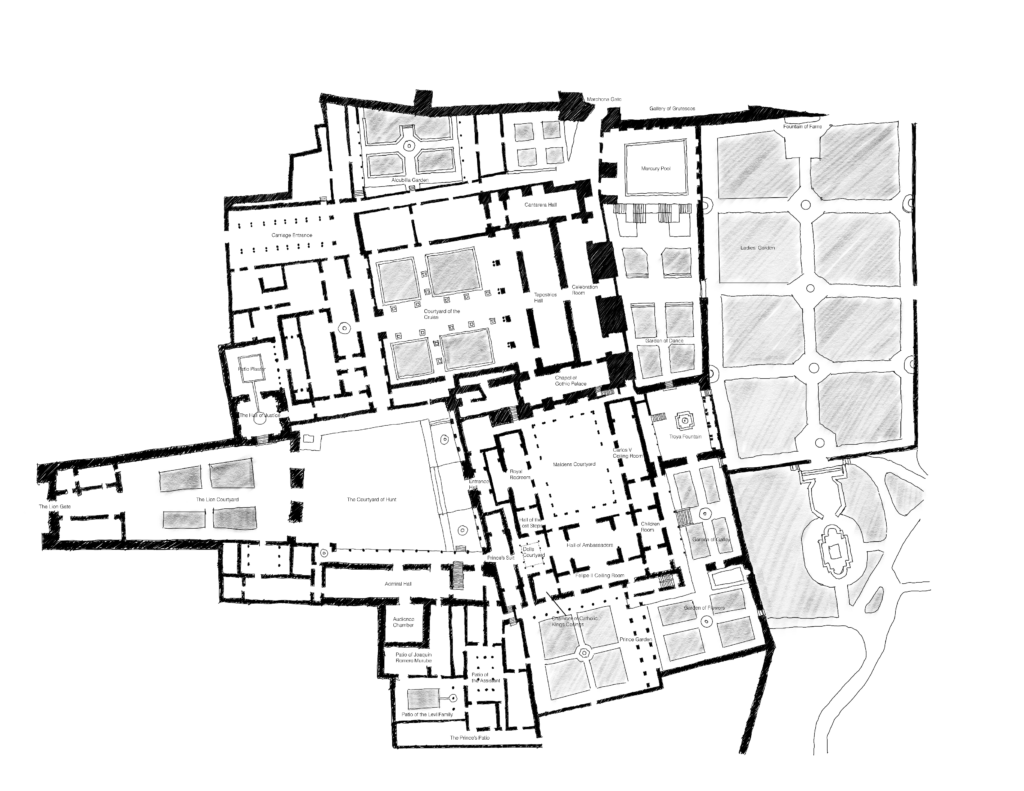

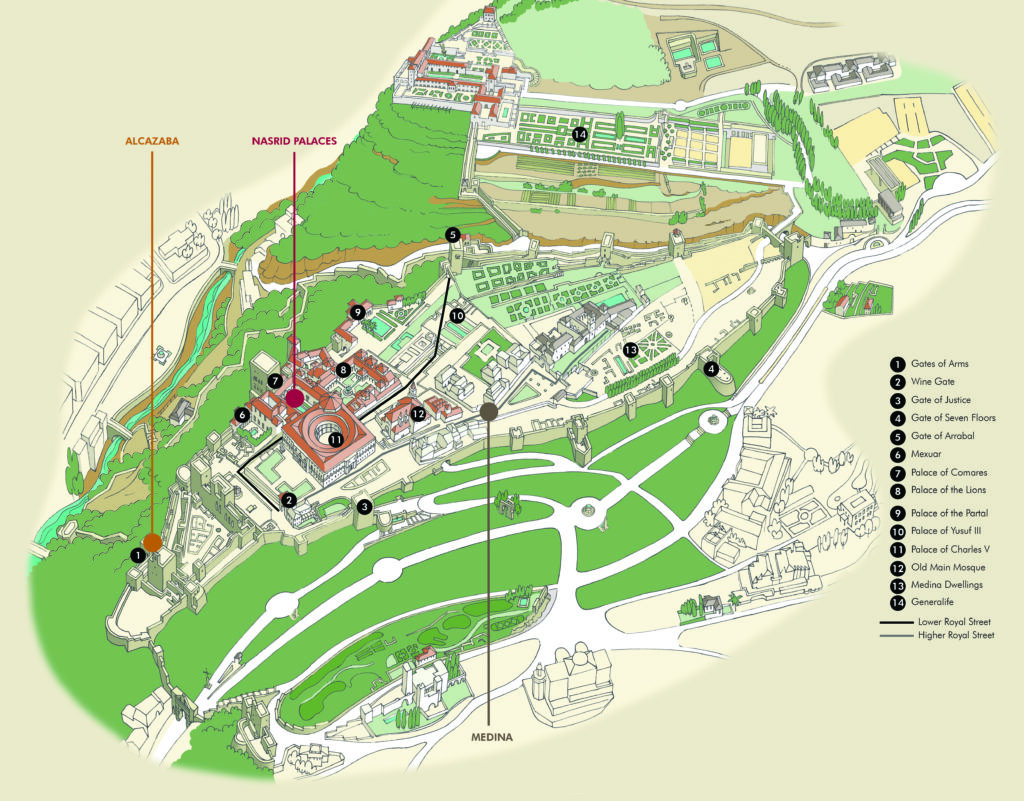

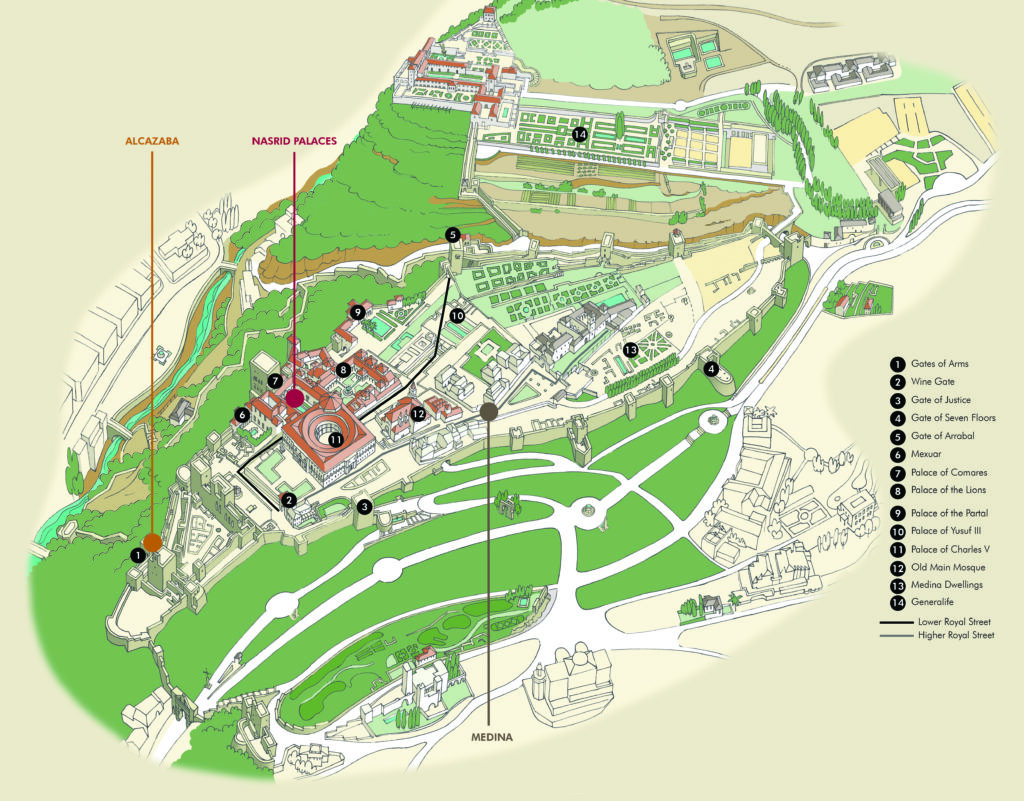

Bağımsız bir saray kompleksi olan Elhamra, üç ana bölümden oluşmaktadır: Alcazaba, Nasrid Sarayları ve Medina. Surlarla çevrili kompleks iki bölgeye ayrılmıştır: Kuzeydoğuda “Aşağı Elhamra” ve güneydoğuda “Yukarı Elhamra”. Bu iki bölge, saray alanından geçen “Aşağı Kraliyet Caddesi” ve Medina’nın tamamından geçen “Yukarı Kraliyet Caddesi” ile birbirine bağlanmaktadır. Ana caddeler daha küçük ikincil caddelerle birbirine bağlanmaktadır. Kompleksin bölünmüşlüğü sadece fiziksel bir ayrımı değil, aynı zamanda iki bölge arasındaki sosyal ve ekonomik ayrımları da yansıtmaktadır.

Komplekse yaklaşırken ilk göze çarpan unsur, üçgen alınlığının üzerinde üç sembolik nar bulunan Rönesans tarzı “Nar Kapısı”dır. Elhamra ağaçlarının oluşturduğu dingin atmosfer ve suyun dinlendirici sesi, kapıdan geçtikten sonra ziyaretçileri içine çeker ve “Adalet Kapısı”na yaklaşırken huzurlu ve davetkâr bir deneyim yaratır. Surlarla çevrili alanın en önemli girişi olan “Adalet Kapısı” derin anlamlar taşımaktadır. At nalı kemerin kilit taşı üzerindeki anahtar ve el tasvirleri sırasıyla Kur’an’ın beş emrini ve cennetin anahtarını sembolize eder [9].

Elhamra kompleksinin ilk bölümü, sitenin en eski kısmı olan Alcazaba’dır. Alcazaba tüm kompleks için savunma amaçlı bir tampon bölge görevi görmüş ve askeri tesislere ev sahipliği yapmıştır. Üçgen planlı yapı çift surla çevrilidir ve çevre boyunca düzensiz bir yerleşimde yükselen sekiz kuleye sahiptir. İki sur seti bir hendeği çevrelemektedir. Bu askeri bölge içinde, tipik Müslüman ev planını sergileyen konut, atölye, depo ve hamam kalıntıları hala görülebilmektedir. Alcazaba’daki her bir kule, hem işlev hem de estetik açıdan her birini birbirinden ayıran benzersiz özelliklere sahiptir.

“Yukarı Kraliyet Caddesi” ziyaretçileri küçük konutlar, hamamlar, idari binalar ve asil saraylardan oluşan Medine mahallesine götürür. Medina’nın mütevazı yapıları ve mimarisi ile doğası arasındaki muhteşem uyum, burayı tüm kompleksin en dikkat çekici bölgesi haline getirmektedir. Alcazaba’da olduğu gibi, eski yerleşimlerin kalıntıları hala belirgindir. Kompleksten mahalleye tek giriş noktası, Fransız birlikleri tarafından havaya uçurulan ve daha sonra orijinal çizimlere göre yeniden inşa edilen “Yedi Katlı Kapı ”dır.

Nasrid Sarayları, lüks ve süslü dekorasyonlarının ötesinde sembolik, yapısal ve mimari bir öneme sahiptir. Farklı inşa dönemleri bu saraylara farklı mimari nitelikler kazandırmıştır. Tüm Müslüman evlerinde olduğu gibi sarayların da dış cephelerinde göz alıcı unsurlar bulunmaz; bunun yerine, zenginlikleri ve ihtişamları duvarların içinde bulunur. Bu tasarım tercihi, inananlar arasındaki eşitlik duygusunu bozabilecek her şeyi gizlemeyi amaçlamaktadır. Sarayların inşası da bu geçicilik kavramını yansıtmaktadır. Ahşap, kil ve sıva gibi ucuz ve kırılgan malzemelerin kullanımı hayatın geçici doğasını sembolize ederek sadece Tanrı’nın ebedi olduğunu vurgulamaktadır. Bu yüzden, yapılar iktidardaki Sultanlar tarafından sık sık değiştirilmiş veya yenilenmiştir.

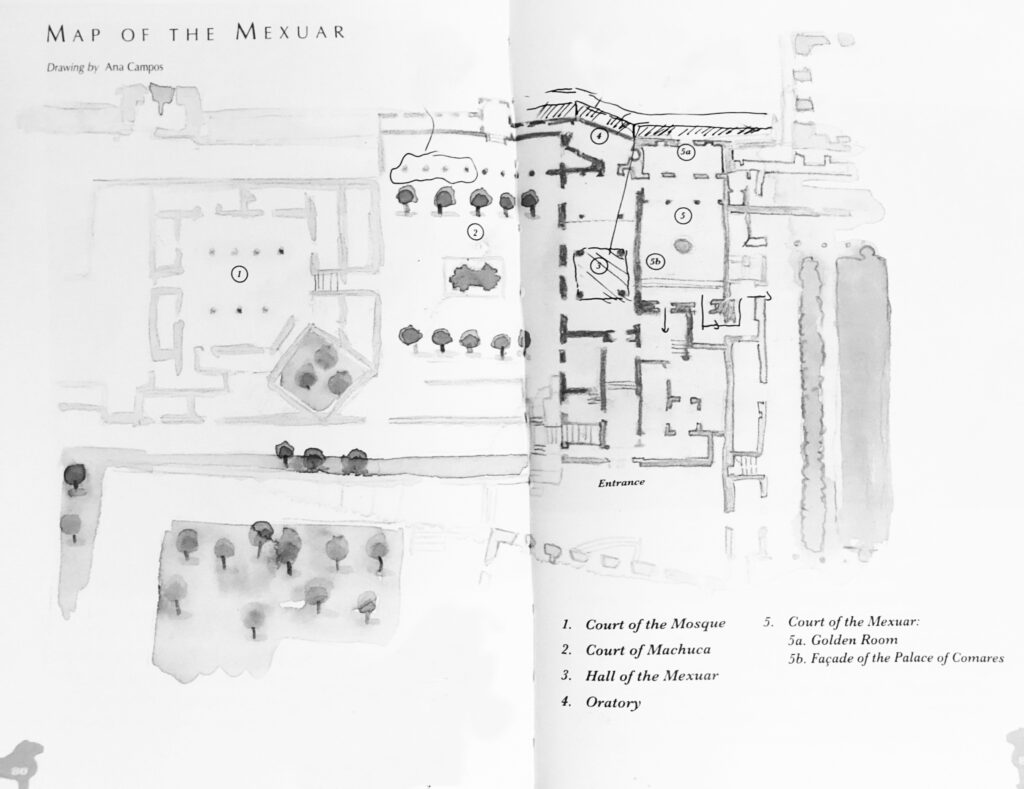

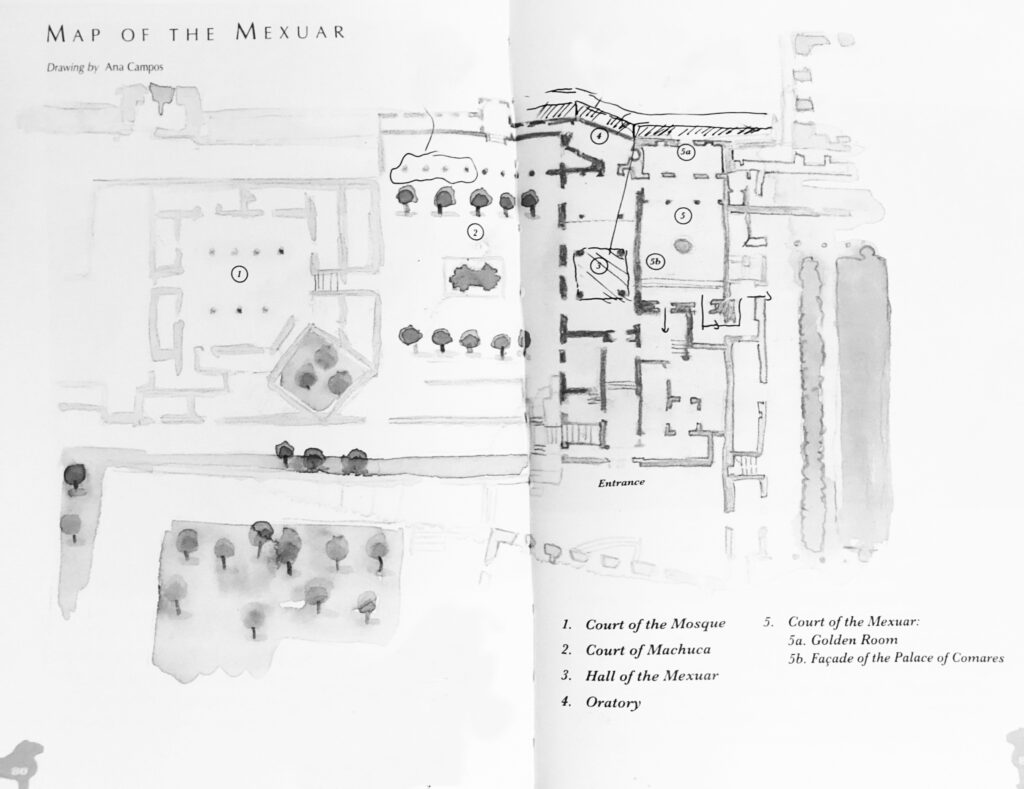

Nasrid saray kompleksi üç ana bölümden oluşmaktadır: Mexuar, Comares ve Leones Sarayları. I. İsmail döneminde inşa edilen Mexuar Sarayı, idari ve bürokratik işlevlere hizmet etmiştir. Bir hitabet kürsüsü, bir salon ve bir mahkemeyi içeren bir adalet mikrokozmosunu temsil etmektedir. Mexuar Salonu bu sarayın en dikkat çekici bölümlerinden biridir. Hristiyan ve Müslüman mimari etkilerinin olağanüstü karışımı ziyaretçileri büyülemektedir. Orijinal olarak dört sütun üzerinde duran yapı, Hristiyanlık döneminde ahşap bölme duvarların eklenmesi ve tavanda yapılan değişikliklerle bir şapele dönüştürülmüştür. Endülüs mimarisinin karakteristik özelliği olarak duvar sistemi üç öğeden oluşmuştur: duvar ve zemin arasında bir süpürgelik, düz bir duvar ve duvarı tavana bağlayan mukarnaslar.

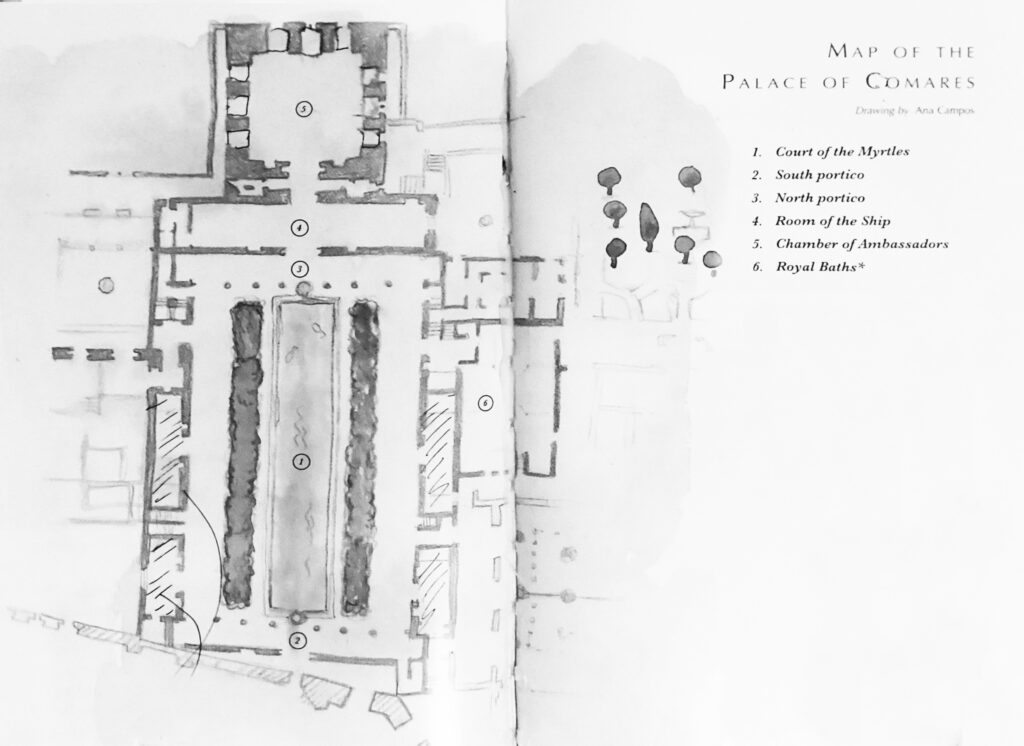

Merkezinde bir çeşme bulunan Mexuar Avlusu, hem bir ayırıcı hem de bağlantı mekanı olarak hizmet vermektedir. Avlunun kuzeyinde altın çatı ve sebka panellerine sahip üç kemerli revaktan oluşan “Altın Oda Portikosu” bulunurken, güneyinde ise merkezinde büyük bir havuz yer alan ve kraliyet hamamlarına ev sahipliği yapan “Comares Sarayı” bulunmaktadır. Konut birimleriyle çevrili Comares Sarayı’ndaki merkezi havuz, güney portikodan kuzey portikosuna kadar uzanan ve Elçiler Odası’nda sonlanan doğrusal düzenlemeyi vurgular. Tüm sarayın en büyük odası olan bu mekan küp şeklinde tasarlanmıştır. Zengin bir şekilde dekore edilmiş dokuz yatak odası, merkezi açık alanı üç taraftan çevrelemektedir. Muhteşem süslemeler ve karmaşık kufi ve el yazısı odanın duvarlarını süslemektedir.

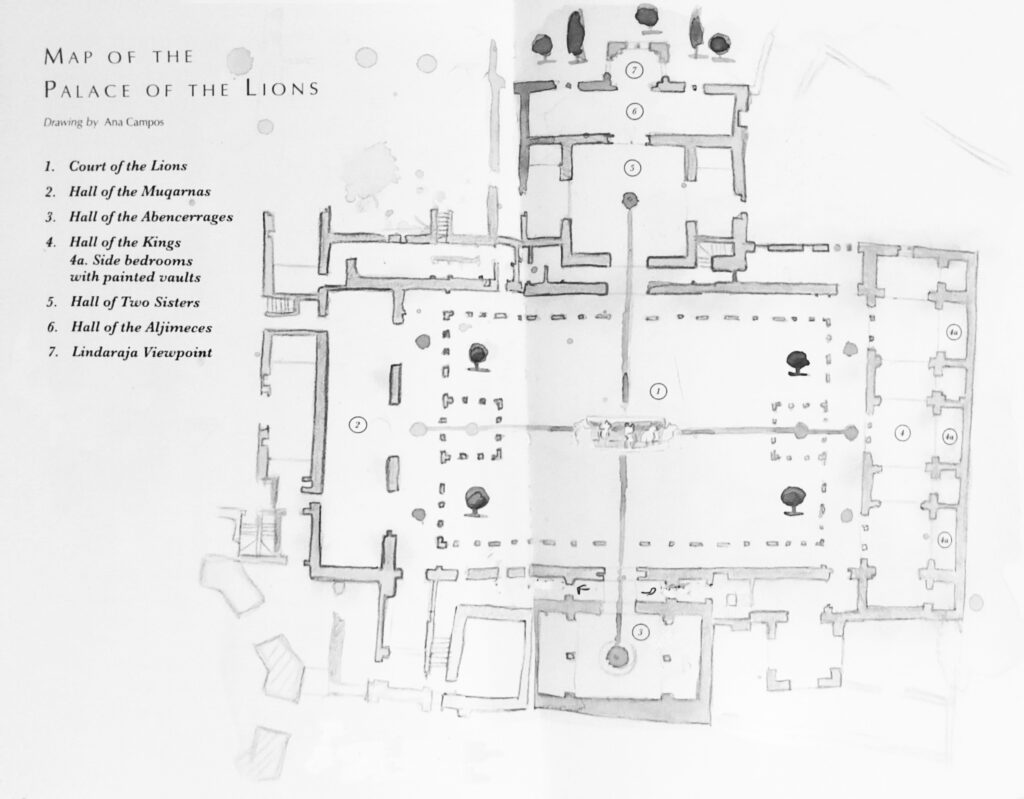

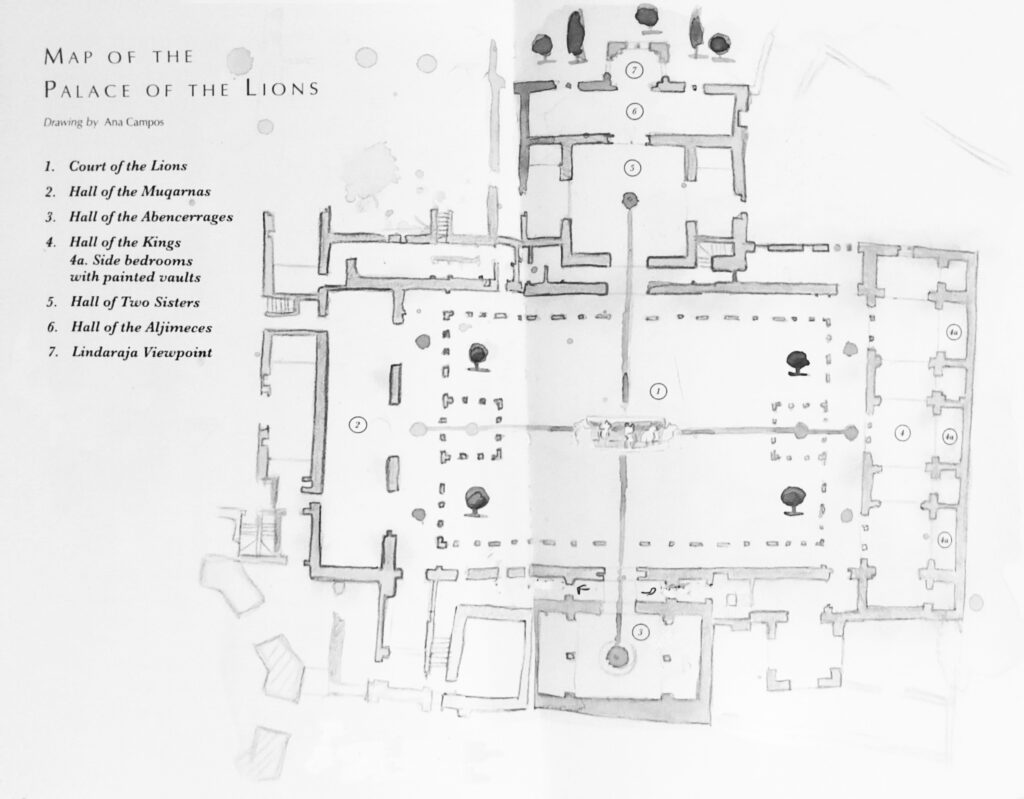

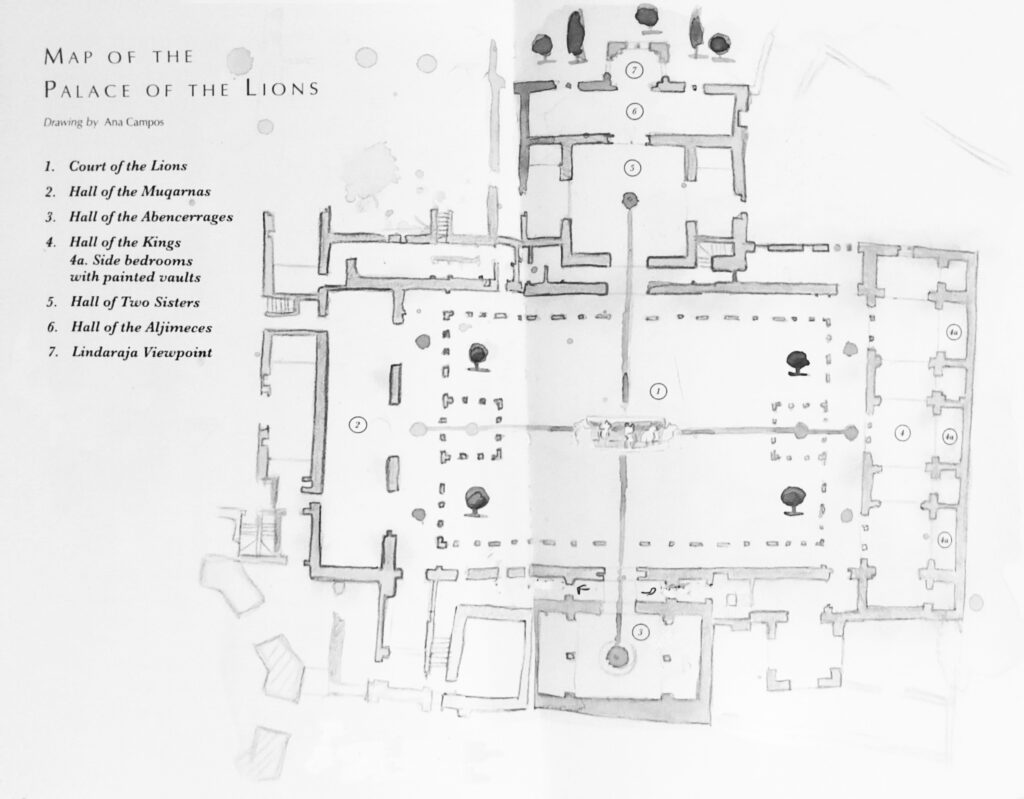

Son saray kompleksi, merkezi bir avlu etrafında düzenlenmiş odalara sahip “Aslanlar Sarayı”dır. Sarayın orijinal girişi “Aşağı Kraliyet Caddesi”nden yapılmaktaydı; ancak şu anki giriş noktası tarihi Hristiyanlık dönemine dayanan Myrtles Avlusu’ndan yapılmaktadır. Merkezi çeşmeden dört yöne ayrılan su kanalları, dört farklı salonun yerlerini işaretlemekte ve yönlendirici unsurlar olarak kullanılmaktadır. Aslanlar Avlusu, Elhamra’nın tamamında en heyecan verici ve tanınmış alanlardan biridir. Kemerler ve girift bir şekilde oyulmuş alçı panellerle birbirine bağlanan 124 mermer sütunla çevrelenen avlu cennet alegorisini sembolize etmektedir [10]. Avlunun dört su kanalıyla bölünmesi, Müslüman Cenneti’nin dört nehrini temsil etmekte ve sembolik olarak dünyayı dört bölüme ayırmaktadır [10]. Bu yapay cennetteki bölümlerden biri, zarif mukarnas işçiliğine sahip tonozlu bir tavanla süslenmiş bir antre ve giriş alanı olarak hizmet veren “Mukarnas Salonu”dur. Ziyaretçileri karşı tarafta karşılayan ve ağırlıklı olarak toplantılar, partiler ve etkinlikler için kullanılan diğer salon ise bir “Krallar Salonu”dur. Güneyde yer alan “Abencerrages Salonu” ve kuzeydeki “İki Kız Kardeş Salonu” sarayın en önemli alanlarıdır. “Abencerrages Salonu”nun tavanı cennetin kanopisini temsil eden büyüleyici bir mukarnas kubbeye sahipken, aslen ikamet için tasarlanan “İki Kız Kardeş Salonu” da detaylı çini işçiliği, mukarnas kubbesi ve çarpıcı alçı duvarlarıyla benzer şekilde keyifli bir atmosfer sunmaktadır.

Elhamra kompleksinin son durağı V. Charles Sarayı’dır. İslam mimarisiyle çevrili bu saray, ziyaretçilerin merakını cezbeden mimari bir çelişki sunmaktadır. V. Charles Sarayı, Nasrid Hanedanlığı tarafından inşa edilen Müslüman yapıların arasında yer alan Hristiyanlığın sembolik bir vasiyeti olarak görülebilir. İhtişamlı bir cepheye sahip kare şeklindeki bina, süslemeden yoksun dairesel bir avluya sahiptir. Avlunun sade görünümü ve cephenin zengin mimari unsurları keskin bir tezat oluşturmaktadır. Bu keskin fark, V. Charles Sarayı ile Nasrid Sarayları arasındaki en belirgin çelişkidir.

Endülüs yolculuğumuzun sonunda Granada’dan ayrılmadan önce Caja Granada’yı ziyaret ediyoruz. Spiral rampaları, eliptik avlusu ve figüratif açıklıklarıyla Caja Granada, mimari iç içe geçme temasını keşfetmek için son durak olarak karşımıza çıkmaktadır. Alberto Campo Baeza tarafından tasarlanan yapının genel tasarımı Hristiyan ve Müslüman mimari unsurlarını harmanlamaktadır. Merkezi açıklığa sahip geniş cephe, Hristiyan mimarisinin çarpıcı özelliklerini bünyesinde barındırırken, sütunlarla desteklenen yürüyüş yollarına sahip sade eliptik avlu, kompleksin önemli bir öğesi haline gelmiştir. Beyaz, sade avlu genel tasarımın dinamik ve canlı karakteriyle harmanlanmaktadır. Zıt stillerin bu füzyonu, iki mimari gelenek arasında dikkate değer bir diyalog yaratmaktadır.

ENGLISH VERSION

Intertwining: Learning from Al-Andalus

“Non-Plus Ultra”, these are the words marking remarkable point in history, associating the “Straits of Gibraltar” with the edge of the known world.That ancient metaphor had been reinterpreted as “Plus Ultra” by Charles V, turning longstanding taboo into an empowering declaration expressing that other side of Atlantic is under domination of Spain [1].

Al Andalus is a multicultural region ruled by various nations and ethnic groups ranging from Vikings, Phoenixes to Romans and Muslims. Due to its geopolitical conditions, the region beared witness the intertwining of different cultures, however the most prominent cultural exchange,which still could be felt and seen today, realized between 8th and 15th centuries when Muslim authorities were in charge. Hence, the essay will explore the “intertwining theory” not only as an social interchange between cultures but also physical demonstration of architecture in different scales and different periods. The essay will be consisted of three sections which each section is dedicated to the visited cities; Seville,Cordoba and Granda.The historical and contemporary architectural treasures will be examined through the eyes of an architect.

Section 1:The Capital

After passing through the narrow city corridors flanked by elegant yellowish Renaissance facades adorned with Mudejar-style ornamentation, visitors are welcomed by a gigantic Gothic-style church situated in a wide open square. La Catedral de Sevilla, a former mosque, stands as one of the iconic structures that blend two different religious architectural styles in Andalusia. While most of the original mosque was demolished to construct the church, the iconic minaret and the courtyard filled with orange trees remain as remnants of Islamic architecture [2]. The cathedral underwent various phases of construction, beginning in the 15th century and completed in the 17th century. This led to a mix of architectural styles within a single structure, including Baroque, Renaissance, Gothic, and Islamic features.

Along the way, climbing to the top of the tower offers a stunning view of the city of Seville below. The openings and niches scattered along the sloped corridors open up new perspectives to experience the city from above before jumping to a new level, which ends up with reaching a peak. The similar feelings could be felt while climbing up the stairs in Tate Modern. Starting from basement level, uninterrupted circulation hub gives visitors to experience the city from different perspectives.

From Plaza del Triunfo, where flamenco melodies seem to follow the rhythmic beat of horse-drawn carriages, conversations dance through the air, and the sounds of water nourish the human soul. The Lion Gate, with its reddish walls dating back to the 11th century, captivates the eye. As you approach the gate, the two observation towers illustrate how the brickwork was carefully combined with small stones to reduce the weight of the structure and absorb structural movements [3].

Before reaching the Courtyard of the Hunt, visitors are guided along a central axis that passes through the Lion Courtyard. Until a fire destroyed it, the theater known as the Corral de Comedias de la Montería occupied the entire courtyard with its elliptical ground floor plan [3] . The current central axis was created by Pedro I and allows visitors a direct view of the main courtyard, which is surrounded by three different eras, three architectural styles, and three facades. The entire complex is a blend of Moorish and Gothic architectural elements, serving as an intertwining point of cultures and humanity within a multicultural structure.

Throughout the experience, visitors can smell the exotic trees, hear the gentle murmurs of water, feel the serenity of nature, and admire the magnificent structures. The Real Alcázar can be identified as an artificial paradise, an oasis in the midst of the city. Once an isolated palace and fortress belonging to a single family or individual, it now offers an atmosphere for breathing, learning, and well-being. In addition to the courtyards bordered by facades with delicate architectural features, a sprawling park and a series of gardens adjacent to the complex provide a rejuvenating escape.

While directing the route from Old town to the opposite side of Guadalquivir River, the aim was to reach to the Torre del Oro, the stone covered facade with gilded inscription attracts the attention even before tower. Prevision Espanola build by Rafael Moneo is a symbol structure in Seville’s contemporary architecture. The office building, currently occupied by Helvetia Seguros, is located on the edge of the city. ”Prevision Espanola” follows the ramparts that date back to the Almohad period [4]. Its wall-like character references the existing Almohad structure through subtle design elements and thoughtful architectural choices. The entire complex serves as a backdrop to the Torre del Oro.The structure’s horizontal design is stressed by a continuous band of windows, horizontal stone strips, and a white cornice made of bush-hammered concrete. A porticoed gallery supported by delicate circular marble columns and curved brick walls evokes the Almohad architecture found in the Real Alcázar. The horizontal marble band divides the facade into upper and lower sections. Resembling a fortified castle, the entrance creates a memorable and figurative impression, reminiscent of observation towers. In this way,the connection to the past is achieved through the facade’s allusions and design features. In terms of materiality and form, the building seamlessly integrates into the urban fabric by pursuing the building principals. By serving as a complementary structure to the Torre del Oro, “Prevision Espanola” highlights the presence of tower. Rear courtyard of the building currently serves a parking area, and does not attract human flow coming from the narrow streets of the city, however, the decent courtyard has powerful potential to be intriguing public space and intertwine the different periods in a common place as in Real Alcazar.

Section 2:The Continuity

The route continues with the region whose Islamic impact on architecture could frankly be seen and felt. This is Cordoba which accommodates historical Muslim bathhouses, the famous Mezquita de Córdoba, and unique small and refreshing green patios filled with flowers and exotic trees. The ancient character of the city is still preserved and housing units in the old town tend to be 2-3 storeys. Organic urban fabric gives an irresistible opportunity to explore the unique beauties on cobblestone paved streets. These streets are either confined by either plastered white walls or Andalusian style stone facades. Puerta del Puente welcomes visitors coming out from the other side of the river Guadalquivir through an ancient Roman bridge which is known as Puente Romano.

Before leading the route towards the world famous landmark, remnants of the historical “Baños del Alcázar Califal” bathhouse, an example of palatial architecture, grab the attention.Built as baths of Caliphal Palace during 10th century, they are example of palatial architecture at the service of emirs and caliphate [5]. “Baños” always combines directional and circulative plan layout. Beyond the physical purification, the ritual is a spiritual relaxation, enhancement of mental health. The ritual starts at the rectangle space “Frigidarium-Cold Room” where the body is prepared for the purification process. Before jumping into “Caldarium-Hot Room” , the body goes into the final preparation space called “Tepidarium-Warm Room”. In this room, the most remarkable architectural and structural details grab attention. Horseshoe arches supported by flamboyant brown and black marble columns are the most prominent feature in the bathhouse. It could be also discovered that the layout of columns form a small arcade around the perimeter of the central marble floor. Natural sunlight penetrates inside the room through a small star shaped skylight on the ceiling. The body’s spiritual voyage ends up at the final destination, the Hot Room. Similar to a warm room, the central space confined by porticoed galleries gives this space its unique identity.

Orange trees spring out from embedded circular pots linked through lineer canals, voices and chirms blend inside a gigantic courtyard confined by 12th century structure. This is Mezquita de Córdoba witnessed the different caliphates, religions, and architectural approaches. Mosque of Damascus had created the topological pattern for the most later mosques by establishing the idea of Islamic “religious space”, a space that reflects a new way of understanding the relationships between man and God. Mosque of Cordoba, on the other hand, opened up a new way for Islamic architecture by reflecting the time, by embracing every person no matter ethnicity or nationality.It is a temple of unity. The diffuse presence of God was materialized in the infinitude of artificial space of the mosque. “Axiality” and “sequentiality” of Christian church (centrality) were replaced by neutral, non-characterized spaces [6]. Need for symmetry imposes a certain order even under the circumstances of abstraction and undifferentiation.

The history of Cordoba Mosque covers almost 10 centuries. The construction of the former mosque dates back to the 8th century, during the reign of Abd Al-Rahman I. Original plan layout was inspired by mosques in Damascus and was based on Basilica plan typology. During the era of Abd Al-Rahman II, the first enlargement was completed and the mosque was retained. However, at first sight, it is noticeable that the base of columns were removed, which belongs to that period. After the construction of the minaret during the reign of Abd Al-Rahman III, the most remarkable and remembered enlargement plan had been carried out during the Caliph Al-Hakam II. Building was extended towards south with new twelve sections, which makes the mihrab and maqsurah special focusses of attention. The most innovative action was the construction of four skylights, the first in the entrance of enlargement and other three preceding the mihrab. The overall appearance of the mosque has been enriched through use of delicate plant motifs as ornamentation, flamboyant marble and mosaic materials.

Almanzor carried out the final enlargement project, and the complex was extended towards the west. In terms of architectural value, the final project didn’t bring tremendous contribution to the complex. It could be recognized that voussoirs of arches have the same stone material and brick material in original arches had been faked out through red painting. Among the forest of columns, the two thick perpendicular walls built by Almanzor imposed a new reading of the mosque. Undifferentiated space and directionality of Al-Hakam II is diluted.

Capilla De Villaviciosa as a virtual door between old and new mosque became an authentic threshold. Three bays of the axial nave are defined by a pair of columns in the central opening.The mechanism of overlapping took on a definitive importance for the perforated walls, converted into three dimensional structures. Architectural construction reached its higher expression in complexity and beauty.

Cordoba Mosque is a system of aqueduct walls that run perpendicular to the qibla , and ultimately generate the spatial experience. Horseshoe arches are supported by semicircular arches in order to reach a higher roof and bright space.The formal structure depends on the intersection of both systems. Moreover, the definition of space by columns is a clear expression of the new religious space, neutral and undifferentiated. Overlapped architectonic forms result from an interaction between simple elements, each with their own autonomous significance, merging into a new whole. The element (Modillon de Rollos) resolves the higher part of the capital, where pillar, horseshoe arch and capital column converge. This element solves the conjunction issue, a transition from square base to rectangular base [7].

Longitudinal church was placed on the boundary between Abd-al Rahman II and Al Hakam II mosques, which interrupted the axis of Al Hakam mosque. Respect for the grid of columns can be appreciated in the plan of gothic precinct. Horizontal loads of doors and the access to the nave were absorbed by a series of small rear chapels and by a pre-portico defined entrance hall. Continuity had broken. The Mihrab axis was used as the cathedral entrance.

Section 3:The Palatine City

The final destination of the journey is Granada, home to historical and contemporary architectural treasures such as the Alhambra Palace, Caja Granada, and the Bathhouses. The Alhambra, which means “red castle,” served as the residence of the Nasrid dynasty. The founder of the Nasrid dynasty, Muhammad I ibn Nasr, abandoned the dangerous Alcazaba Cadima in Albaicin and moved his residence to the other side of the Darro River [8]. This independent palatial city consists of three main sections: the Alcazaba, the Nasrid Palaces, and the Medina.The enclosed complex is divided into two areas: “Low Alhambra” in the northeast and “High Alhambra” in the southeast. These two zones are connected by Lower Royal Street, which traverses the palatial area, and Higher Royal Street, which runs through the entire Medina. The primary streets are linked via smaller secondary streets. The complex’s division reflects not only a physical separation but also social and economic distinctions between the two zones.

While approaching the complex, the first thing that catches the eye is the Renaissance-style “Gate of the Pomegranates,” which features three emblematic pomegranates atop its triangular pediment. The serene atmosphere of Alhambra’s woods and the soothing sounds of water immerse visitors after they pass through the gate, creating a peaceful and inviting experience as they approach the Gate of Justice.The Gate of Justice, the most significant entrance within the walled enclosure, carries deep meanings. The key and hand depictions on the keystone of the horseshoe arch symbolize the five precepts of the Quran and the key to paradise, respectively [9].

The first section of the Alhambra complex is the Alcazaba, which is the oldest part of the site. Alcazaba served as a defensive buffer zone for the entire complex and housed military installations. Its triangular layout is surrounded by double ramparts and features eight towers that rise unevenly along the perimeter. The two sets of ramparts enclose a trench. Within this military district, remnants of dwellings, workshops, storehouses, and baths are still visible, showcasing the typical Muslim house plan. Each tower in Alcazaba has unique characteristics that distinguish them from one another, both in terms of function and aesthetics.

Higher Royal Street leads visitors to the Medina neighborhood, which consists of small dwellings, bathhouses, administrative buildings, and noble palaces. Medina’s modest structures and the magnificent harmony between its architecture and nature make it the most remarkable area of the entire complex. As in Alcazaba, remnants of old settlements are still evident. The only access point to the neighborhood from outside the complex is the “Gate of Seven Floors,” which was blown up by French troops and later reconstructed based on original drawings.

The Nasrid Palaces hold symbolic, structural, and architectural significance that goes beyond their luxurious and ornate decorations. Different periods of construction gave these palaces distinct architectural qualities. Like all Muslim homes, the palaces do not feature eye-catching elements on the outside; instead, their richness and splendor are found within their walls. This design choice aims to conceal anything that might disrupt the sense of equality among believers.Their construction also reflects this notion of temporality. The use of inexpensive and fragile materials such as wood, clay, and plaster symbolizes life’s transient nature, emphasizing that only God is eternal. As a result, the structures were frequently modified by the ruling Sultans.

The Nasrid palace complex consists of three main sections: the Mexuar, Comares, and Leones Palaces. The Mexuar Palace, built during the reign of Ismail I, served administrative and bureaucratic functions. It embodies a microcosm of justice, featuring an oratory, a hall, and a court. The Hall of Mexuar is one of the most remarkable sections of this palace. The remarkable blend of Christian and Muslim architectural influences captivates visitors. The original four-column structure was transformed into a chapel during the Christian period, with the addition of wooden partition walls and modifications to the ceiling. They built a choir, added new side windows, and installed a new floor during this time.A characteristic feature of Andalusian architecture, the walls are divided into three sections: a skirting board between the wall and floor, a plain wall, and muqarnas that connect the wall to the ceiling.

The Court of Mexuar, featuring a fountain at its center, serves as both a dividing and connecting space. It is bordered by the Portico of the Golden Room, which has three arched porticoes with a beautifully decorated golden roof and stunning sebka panels on the north side, and the Palace of Comares to the south, which includes a central large pond, royal baths, and exquisite decorative work.The central pond in Palace of Comares, flanked by residential units, emphasizes the linear arrangement from the south portico to the north portico, culminating at the Chamber of Ambassadors. This chamber, the largest room in the entire palace, is designed in a perfect cube shape. Nine richly decorated bedrooms surround the central open space on three sides. Magnificent ornamentation and intricate kufic and cursive script adorn the room’s plaster.

The final palace complex is the Palace of the Lions, which features rooms arranged around a central courtyard with a fountain. The original entrance to the palace was from Low Royal Street; however, the current access point is through the Court of the Myrtles, which dates back to the Christian era. The water canals that branch from the central fountain in four directions mark the locations of the four different halls, serving as directional elements or routes. The Court of Lions is one of the most exciting and recognized spaces in the entire Alhambra. It is bordered by 124 marble columns connected by arches and intricately carved stucco panels, creating a courtyard that symbolizes a garden, or an allegory of paradise [10]. The division of the court by the four water channels represents the four rivers of Muslim Paradise, symbolically dividing the world into four parts. One of these sections in this artificial paradise is the Hall of the Muqarnas, which serves as a vestibule and entrance space adorned with a vaulted ceiling featuring delicate muqarnas’ work.

The Hall of the Kings, primarily used for meetings, parties, and events, greets visitors in the opposite direction. Meanwhile, the Hall of the Abencerrages, located to the south, and the Hall of Two Sisters, to the north, are the most significant areas of the palace. The ceiling of the Hall of the Abencerrages boasts a captivating muqarnas dome that represents the canopy of heaven, while the Hall of Two Sisters, originally intended for residence, offers a similarly pleasurable atmosphere with its detailed tile work, muqarnas dome, and stunning stucco walls.

The final stop in the Alhambra complex is the Palace of Charles V. Surrounded by Islamic architecture, this palace presents an architectural contradiction that piques the curiosity of visitors. The Palace of Charles V can be seen as a symbolic testament to Christianity situated among the Muslim structures built by the Nasrid Dynasty. The square-shaped building features a circular courtyard with a lavish and splendid facade, contrasting sharply with the austere appearance of the courtyard, which lacks ornamentation. This stark difference highlights the most evident contradiction between the Palace of Charles V and the Nasrid Palaces.

Before leaving Granada at the end of our Andalusian journey, we visit Caja Granada. With its spiral ramps, elliptical courtyard, and figurative openings, it serves as a final stop to explore the theme of architectural intertwining. Designed by Alberto Campo Baeza, the overall design blends Christian and Muslim architectural elements. The grand screen facade with its central opening embodies the striking characteristics of Christian architecture, while the secluded elliptical courtyard, with walkways supported by pillars, represents a key feature of the complex. The white, austere courtyard harmonizes with the dynamic and vibrant character of the overall design. This fusion of contrasting styles creates a remarkable dialogue between the two architectural traditions.

Metin Kaynakları/Text Sources

[1] Manuel A.H. Garcia, The Royal Alcazar of Seville: Ten Centuries of History (Grupo Editorial Sial Pigmalion S.L.,2023),152.

[2] Alberto Piernas Medina “La catedral más grande del mundo tiene 23.500 m2 y está en España (y es mayor que la Basílica de San Pedro de Roma)” ,AD Espana, November 13,2024, https://www.revistaad.es/articulos/la-catedral-mas-grande-del-mundo-esta-en-espana.

[3] Manuel A.H. Garcia, The Royal Alcazar of Seville: Ten Centuries of History (Grupo Editorial Sial Pigmalion S.L.,2023),29.

[4] Francisco G.D. Canales & Nicholas Ray, Rafael Moneo: Building, Teaching,Writing (Yale University Press,2015),69.

[5] “Baños del Alcázar Califal” ,La Delegación de Cultura del Ayuntamiento de Córdoba, accessed March 16,2025, https://cultura.cordoba.es/equipamientos/banos-de-alcazar-califal

[6] Francisco G.D. Canales & Nicholas Ray, Rafael Moneo: Building, Teaching,Writing (Yale University Press,2015),269.

[7] Francisco G.D. Canales & Nicholas Ray, Rafael Moneo: Building, Teaching,Writing (Yale University Press,2015),273.

[8] Ana S. Peinado & Angel S. Peinado , The Alhambra (Ediciones Miguel Sánchez, S.L.,2014),8-9.

[9] Ana S. Peinado & Angel S. Peinado , The Alhambra (Ediciones Miguel Sánchez, S.L.,2014),27.

[10] Ana S. Peinado & Angel S. Peinado , The Alhambra (Ediciones Miguel Sánchez, S.L.,2014),125.

Resim Kaynakları/Figure Sources

(1) Tate Modern Physical Model , https://uk.pinterest.com/pin/105905028707983838/

(2) Prevision Espanola ,photo by Michael Moran,1987, https://lacasadelaarquitectura.es/en/resource/edificio-de-oficinas-prevision-espaola/fa82619c-57c6-4398-8865-79404e028fd6

(3) Alhambra Complex, The Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife,https://www.alhambra-patronato.es/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Plano_General.pdf

Kaan Servi; Lisans (2019) eğitimini İTÜ’de, yüksek lisans (2022) eğitimini UPC’de tamamlamıştır. Adaptive Re-use üzerine yazdığı tez çalışması enstitü tarafından Mükemmeliyet Ödülü’ne layık görülmüştür. Mimari felsefe olarak “research by design” temasını benimseyen Servi, çalışmalarında sürdürülebilirlik temasını işlemekte ve mimariyi bir sentez olarak değerlendirmektedir. Aktif olarak profesyonel çalışmalarını sürdürmektedir.